POSTERIOR CRUCIATE LIGAMENT RUPTURE

The posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) is one of the less commonly injured ligaments and located in the back of the knee. It is one of several ligaments that connect the femur (thighbone) to the tibia (shinbone).

Up to 95% of the function of the ligament is to restrain posterior tibial displacement (posterior drawer). Additionally functions as a restrain to excessive lateral and medial opening of the knee joint in extension.

ANATOMY

Two bones meet to form your knee joint: your thighbone (femur) and shinbone (tibia). Your kneecap sits in front of the joint to provide some protection.

Bones are connected to other bones by ligaments. There are four primary ligaments in your knee. They act like strong ropes to hold the bones together and keep your knee stable.

The PCL origin is a comma-shaped area on the medial femoral condyle. Its insertion is located in an oval midline shallow sulcus below the articular surface of the tibia.

Two components (bundles) of the PCL are commonly recognized: a thicker, stronger anterolateral portion that is tight in flexion and smaller posteromedial portion that is tight in extension.

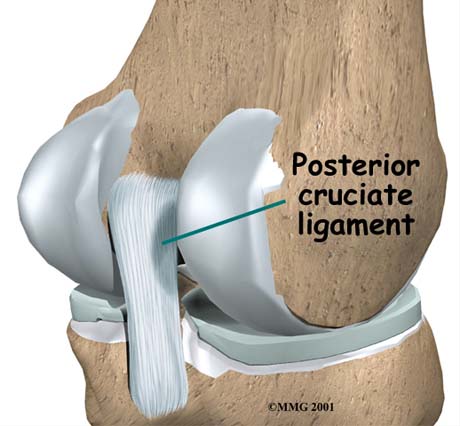

Τhe posterior Cruciate ligament.

Knee MRI: The posterior cruciate ligament is intact (arrow)

Knee MRI, posterior view, intact posterior cruciate ligament (arrow)

MECHANISM OF INJURY

The mechanism of injury is most commonly a posteriorly directed force to the anterior of a flexed knee, the so-called dashboard injury. In athletics, such injuries can be caused by a fall on a flexed knee with a plantarflexed foot.

More rarely, PCL injuries can result from hyperextension or hyperflexion and are often associated with multiple ligament injuries. Unlike ACL injuries, the patient with a PCL injury does not usually feel a pop and the athlete may not be able to describe exactly how or when the injury occurred.

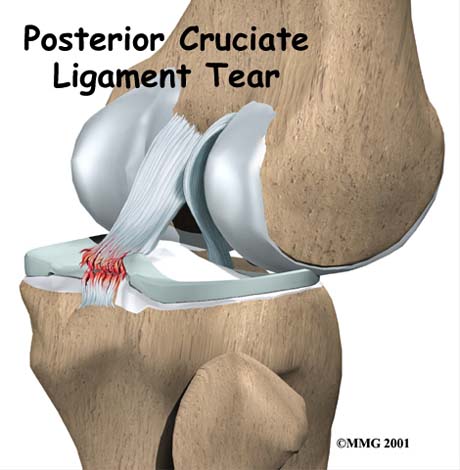

Posterior cruciate ligament rupture due to trauma.

SYMPTOMS

The typical symptoms of a posterior cruciate ligament injury are:

• Pain with swelling that occurs steadily and quickly after the injury

• Swelling that makes the knee stiff and may cause a limp

• Difficulty walking

• The knee feels unstable, like it may "give out"

DIAGNOSIS

The history and physical examination is probably the most important tool in diagnosing a ruptured or deficient PCL. During the physical examination, the doctor will check to see if the tibia moves too far back on the femur.

Tests are also done to see if other knee ligaments or joint cartilage have been injured. The doctor may order X-rays of the knee to rule out a fracture. Ligaments and tendons do not show up on X-rays.

Clinical examination, posterior draw test for the knee instability due to posterior cruciate ligament rupture.

The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan is the most accurate test without actually looking into the knee. The MRI machine uses magnetic waves rather than X-rays to show the soft tissues of the body.

This machine creates pictures that look like slices of the knee. The pictures show the anatomy, and any injuries, very clearly.

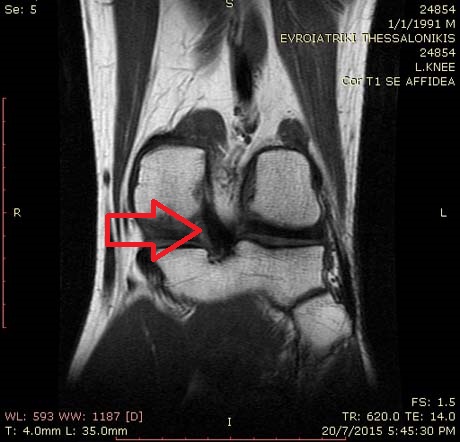

MRI demonstrating a disrupted PCL (red arrow) with posterior sag.